Why cools things flump.

You haven’t thought about a Segway in a long time. You’re not even sure they still make Segway’s anymore – that is, until you walk downtown and see a fellow in a helmet leading his pod of gliding chariots over the bumpy asphalt.

No, the Segway is not extinct. But it is something of a dinosaur, and by now its uses have apparently been trimmed to urban tours and mall security. But why? Clearly this wasn’t the Segway’s manifest destiny.

If I remember rightly, once upon a time the Segway was declared the poster vehicle of personal transportation. When it first swerved onto sidewalks, it was considered a feat of modern engineering. Snug between its two donut wheels and podium-esque handlebars was an advanced counter-balancing system that propelled you as you leaned forward, and slowed you as you leaned back.

It was magical. And well designed – it had what designers call ‘good affordance’ – meaning it was intuitive to operate; it showed you how to ride it. Even by today’s standards it wasn’t clumsy. It may not have been as sleek as the modern scooters, or as zippy as whatever that new thing is that looks like a foam roller with foot stands. But still, the Segway got around, and any skeptic who ever stepped aboard admitted the same; it was delightful.

I have a soft spot for the Segway, and for things in general that don’t hit their mark though they try. It sounds like me much of the time. But to spin this soft spot into another question: why do some amazing things become amazingly lame? Why do cool things flounder?

Undoubtedly there are a dozen ways to mince the question, but for the sake of this post I’m going to entertain a clue from the late, eminent Stanford sociologist, Rene Girard. Girard, dubbed the ‘Darwin of the social sciences’ was a trailblazing thinker on the topic of human desire. He became famous for his ‘mimetic theory’, or mimesis, which holds that humans are fundamentally imitators and who desire through imitation.

That humans imitate one another is an insight as old as Aristotle – but where Girard builds on Aristotle is his insistence on mimesis; the observation that most of our imitating and desiring is unconscious or pre-rational. According to Girard, imitation is an instinct so immersive and second nature we hardly think about it. It’s like breathing, or accounting for gravity. Although this idea is consonant with much of the bias and behavioral economic literature to surface in the past few years, I’m partial to Girard’s theory because it paints a more lucid picture of the ‘geometry’ of desire.

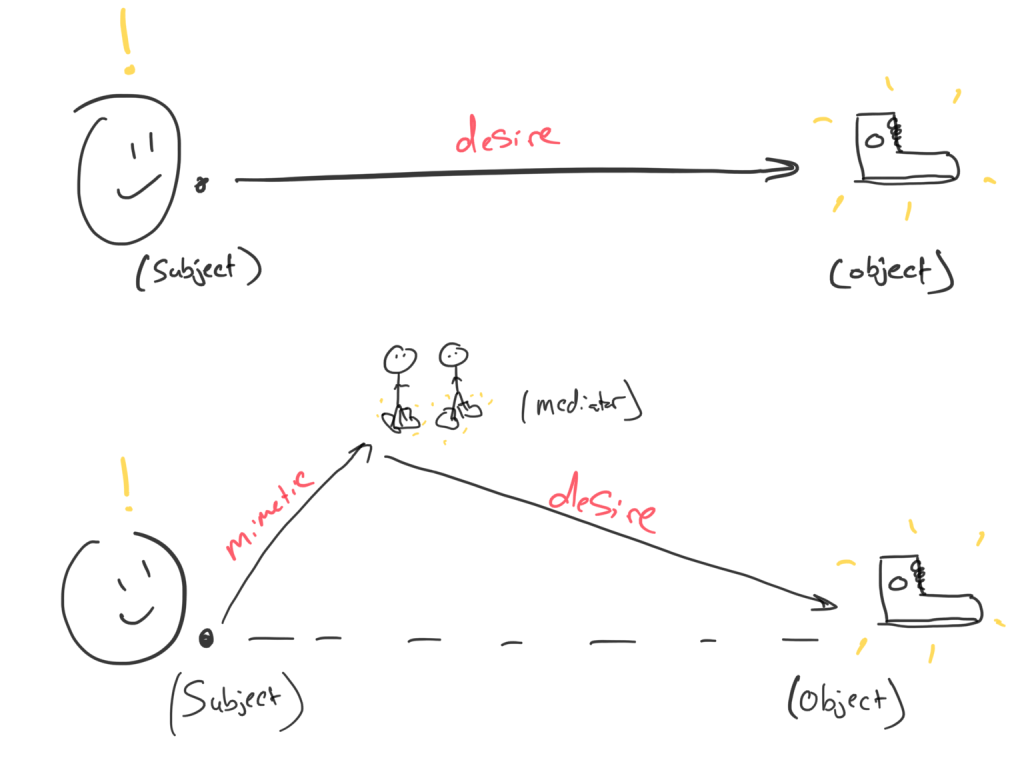

Here’s what I mean: when we think of how desire works, or how it looks, we typically imagine it as a straight line existing between the subject (the person) and the object (the thing they want). You see something. You like it. You want it. Girard says that instead of imagining a straight line, we should imagine desire as a triangle. In the triangle there is a third role, a mediator, or model, who stands between the subject and object, reflecting desire.

Mediators are people and things we imitate. Mediators can be celebrities we imitate consciously ie. I want this pair of kicks because Lebron wears this pair of kicks. But more often and more subtly, our mediators are those closest to us: our peers, our friends, our social network, the startup sharing the office next to us. These are the ones we imitate unconsciously.

And because we are constantly imitating, they have tremendous influence on the way we live. They ‘bend’ and shape our desires, and we in return do the same. Like pure light entering a prism, our desires are refracted and colored by one another, creating a kaleidoscope of wants.

So what does this have to do with the Segway? I believe the Segway’s demise was due in part to a mimetic misfire. It floundered because it had no compelling models. I don’t mean specifically a favorable celebrity endorsement. You could argue that Beyoncé on a Segway or Tom Brady on a Segway would have lit a fuse and turned things around – but I’m referring more so to the everyday Segwayer you never saw; the cool, anonymous street rider who would have passed you on your own neighborhood block and made you do a double take. Segway never had that rider.

The most it had by way of popular endorsement came in the form of a Hollywood lampoon, in the movie “Paul Blart, Mall Cop”. Blart, played by actor Kevin James, is a fumbling hero- a sluggish, inept officer who sallies around the mall on his faithful steed, the Segway. He is an anti John Wayne. The model you do not imitate. The model you imitate in reverse.

Granted, mimetic theory is not the whole of the picture of why good things flounder. It must be taken with a grain of salt. Girard himself warns against an overly formulaic approach to applying the theory and understanding the geometry of desire. The triangle is a metaphor, not a mathematical proof. Still, if his theory has any action value I believe it’s because it offers a unique optical advantage. It helps one see below the flurried surface of transactions and trends, down to the core building blocks of desire. In a way it’s like business x ray. And when it comes to imitating the question is not if, but who.

I’m sad to say Segways are old tread these days. They’ve been overtaken by the new prince of pavement: scooters. Scooters are back. Buzzing. Careening. And they’re not your driveway variety either. Time will tell if they sweep the whole crowd off their feet, but for now their destiny depends at least on one thing: who’s riding, and who’s watching.