Whenever I sit down to write something that I believe, at face value, to be straightforward, bite-size, and clear, I find that midway into the writing of it, the subject magically expands and grows in shape like a slowly filling water balloon.

The topic, whatever it is, usually contains more than I allow. This happened in my last post on practice; as I wrote I began to make nifty connections, recall relevant quotes, and overturn all sorts of interesting rocks of reference. It’s gratifying, this exploratory leg of the journey, but at some point the challenge becomes deciding whether to keep filling the balloon or when to switch it out for another.

Either way, you can’t keep it all and something has to go. Some people call this method of exclusion ‘killing your darlings’, but I’ve never liked that phrase. It’s too lurid-sounding for my taste, and I’ve seldom thought of my trimmed words or ideas as darlings so much as compost, little organic bits that might become useful again one day.

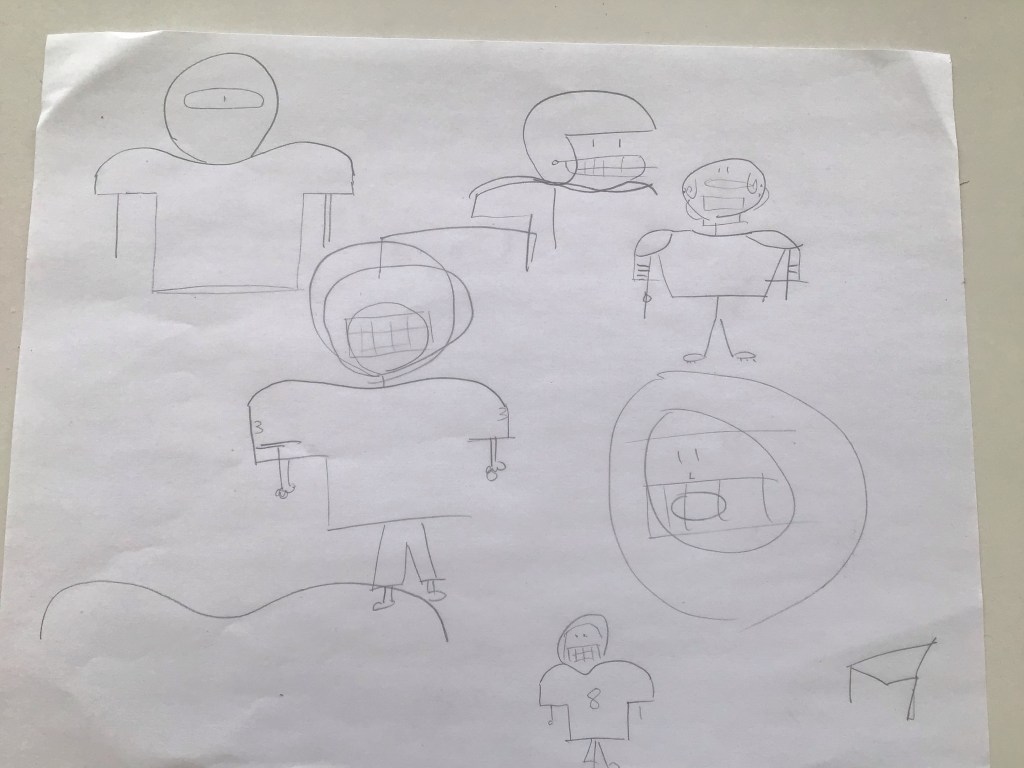

At any rate, when I’ve polished my post satisfactorily, I’m in the habit of drawing a doodle that brings it all together. Besides adding my own quirky visual flair to the posts, these doodles are also my stabs at getting better at sketching. They’re practice.

For the last post I decided to draw peewee football players, an image inspired by the opening story. Simple enough, right? I thought so too, initially, but for the life of me I could not draw a helmet. My early attempts kept looking like horseshoes or cyborgs or tomatoes.

Eventually I caved and googled some ideas. My final doodle was no Rembrandt, but it was better than where it started, and in the spirit of Show and Tell, I wanted to share a couple of those early takes: proof that 1. Practice looks ugly, and 2. The challenge in drawing-writing-thinking, is not making the connection, per se, but showing others how you made the connection so they can see too.

To draw a helmet, draw a hundred unhelmets first.