I’ve been working on a new story the past few months. It’s about a ho-hum security guard who unexpectedly finds himself in possession of a strange ‘gift’ or ability- one he doesn’t quite understand and which begins to complicate his life and the lives of others. Being somewhere in the middle of the plot, I have a long way to go, but I wanted to pop my head up and share a souvenir from the creative process.

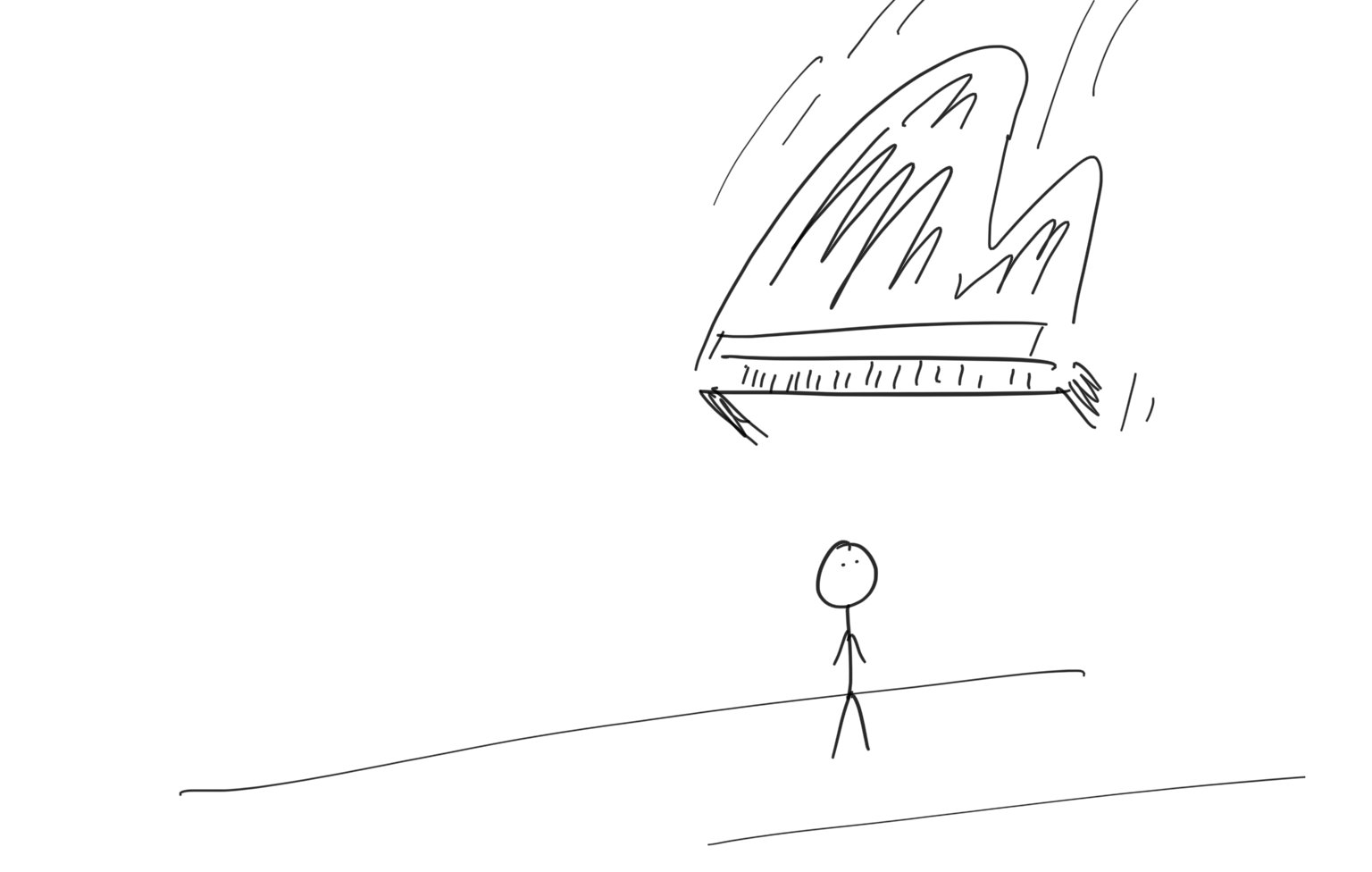

This souvenir is a note I’ve had scribbled at the top of my whiteboard for the past few weeks. It reads: ‘Don’t be afraid to break a glass’, which translates (in my mind) to: Don’t be afraid to make bad things happen. To let the piano fall from above. I wrote it when I realized I was entering the treacherous middle of the story. Middles are hard. They’re disorienting. Time gets swampy. They can easily stretch on for too long and put readers (and writers) into a narrative coma.

There was something else too. I felt my main character was turning cardboard. He was just there, occupying space, being pushed from scene to scene like a slow-moving cow. This is the rut I find myself in. But it’s not a bad rut. On the contrary, it’s forced me to rethink some of the basic elements of storytelling.

One of those elements, as I referred to above, is tempo control; how to move a story along, and how to let a story move itself along. Too fast, too many disasters strung together, and you risk underbaking the characters. You jerk the audience around, urging them to sympathize with people they can hardly imagine walking and talking. The characters turn out to be not characters but caricatures, puppets. Not actors; merely reactors.

On the other end, the story can move too slow. Seemingly nothing’s happened though you’re 50 pages in. Or all the scenes begin to blur together. The author dances from psychological insight to lush description, but there’s no action. Everything is contrived from the inner life of the character, or the landscape. Here too, the narrative tension slackens, yawns set in, etc.

I’m not saying one of these is worse than the other. Both are tricky to navigate. Of these two extremes I’m prone to the second. In fact, when I finished my first book I had to repeatedly forewarn my grandmother that my story was going to be much slower than what she was used to. She is, after all, a Jack Reacher woman. She wants blood, bullets, and a pile of bodies on the floor before she goes to bed.

And I don’t blame her. Actually, I must learn something about this. I must learn how to feed people to the sharks, so to speak. The reason is that it’s very easy for a story to devolve into a mere reporting of events. This ‘drift’, if I may call it so, is unconscious. It happens slowly, seeping in one or two ways. One is under the assumption that a character can, more or less, create their own fate. That they will ‘choose’ their way and develop ‘naturally’, in the course of things, without much tampering from outside. The other way one ‘drifts’ is more innocent. You come to like the character. You get attached. And so you want to protect them from bad things.

But this is fatal. It’s fatal in the art of fiction. And it’s fatal in the art of life.

The only way that people grow is through challenge. Some challenges are self-created; one decision leads to another and another. The plot thickens. But many, and sometimes the most important are sent to them. They break in. They come uninvited. To test the character, to see what they’re made of. The plot thickens again. This is what I’m working on.

Note to self: Don’t be afraid to break a glass.